Wednesday, February 24, 2010

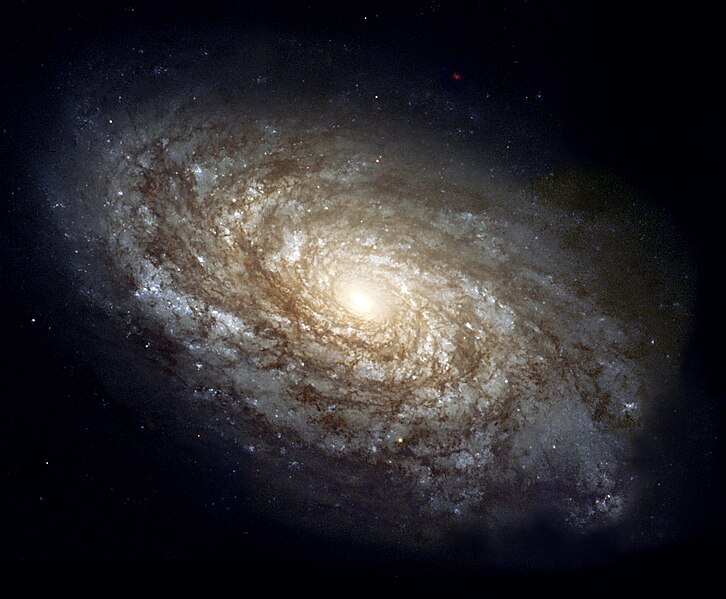

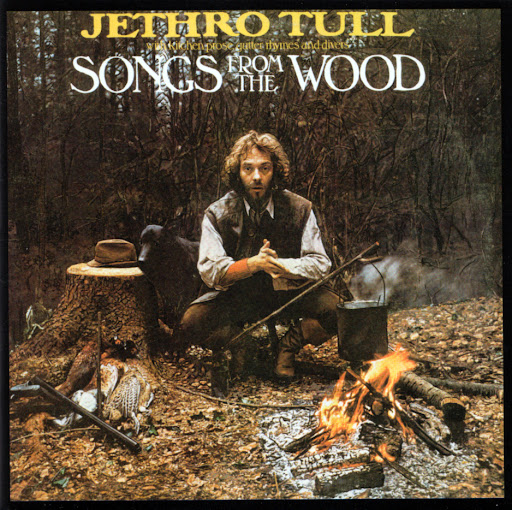

The Woods, My Temple

Several years ago a movie called The Blair Witch Project came to theaters, and it became an instant cult film. It caught a certain sort of zeitgeist among suburban youth, playing upon the latent fears of a whole generation of white kids suffering from a severe lack of experience of the natural world in their upbringing. When I saw it with my friend to fulfill a sense of curiosity about the craze for this "home-made" horror film, I couldn't get caught up in it. In fact, I found the premise of the film insulting to what for me was most sacred. You have to imagine what it would be like for a person, say, raised in a traditional Christian denomination, where the physical structure of a church had always been a place of social warmth, comfort, and fellowship, and then experiencing a viewpoint where it is presented as just the opposite but without any foundation in fact. To leave this metaphorical scenario, I had been lucky enough to have grown up in the generation before the one that found The Blair Witch Project so compelling. I had grown up in the country, and for me, the woods had always been a place that brought me peace, inspiration, and a sense of wholesome refuge. The film I saw was an ignorant vilification of the woodland realm and its aura. I felt like I was seeing the ugly head of anti-nature Puritanism rearing up again, in a "cooler", "more hip" form. For the Puritans, the woods was the place of evil, the devil, the source of destructive wild energies, chaos. They too vilified the wilderness as a place of satanic religion. They failed to grasp that, in the woods (or forest, if you prefer), the presence of God can be felt far more powerfully and pervasively than in the artificially-created environments of sanctioned human activity. What I don't like about films such as this, is that it may have crystallized a viewpoint, perhaps subconsciously, in a generation of people, who now are working their way up the ladders of the professional workforce. They are making decisions or supporting decisions about how much of the natural environment gets preserved and how much of it gets erased. They may not entertain the superstitions of New England's old Puritans, but they may harbor an ill-informed prejudice that the places of wild nature are somehow not wholesome. For such people I can only say their souls are as ill-nourished as the proverbial philistines toward the world of art. Nature is the deepest well of aesthetic beauty. Nature unbound is the ultimate source of all lasting art. It is also a place that the fortunate among us think of as a temple, a place of original worship, where the imagination and spirit of homo sapiens must first have taken form.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment