Sunday, February 28, 2010

The Link of the Unhindered Roamer

Once upon a time the land and its spaces had three functions: as a stage for life's interactions, to provide a place for one's home, and as a means for supporting life itself. If this seems blandly obvious consider how it is no longer so simple. You must now only reside and move within the specific space that you rent or own, or in public spaces, which usually have a set of strict conditions (e. g., only at certain hours, only if you are potential client or customer, only if you're not loitering, only if you're not soliciting, only if you're not speaking to the public, only if you are dressed according to desiginated standards, only if you are not attracting a crowd, only if your presence can in no way be construed as an obstruction of commerce. etc., etc.). But what I'm really driving at in this essay is the loss of something that was taken for granted as a fundamental right even as late as the 1950s in this country: the idea that we are all citizens of the same country and therefore have a right to walk across the land of the rural landscape, regardless of who specifically owns each parcel we pass through, and that we might even sit and enjoy the surroundings or even have a picnic with friends on any given open spot, all of this, of course, with the understanding that the wanderer does not in any way harass or invade the relative privacy of the proprietors. This respectful behavior of benign trespass, which most landowners now would consider a heinous invasion, was once deemed perfectly normal behavior for the bulk of our nation's history. It had the effect of encouraging neighborliness and a sense of community. It also afforded a sense of natural freedom that nourishes the human soul. Now we live in this bizarre age of extreme distrust and officious boundary-consciousness that espouse the view that everyone's neighbor is a potential criminal invader rather than a fellow citizen of the land. In my neck of the woods, I have often heard that people feel perfectly within their right to fire upon you with shotguns ( I once worked with some young men and women who were hiking through a region of mixed pastures and woodlands, and when they had settled down to rest from their hike, this very thing happened to them -- fortunately they all escaped unscathed). So what remains to us? Our public parks surely are a place where one may get back a little bit of a sense of the spacious natural freedom our forebears once enjoyed, but the most accessible of these (the state parks) are underfunded, so their pathways are a wreck, and because of staffing cuts in rangers, it is no longer safe to camp in most of them. The national parks, on the other hand, are becoming more and more regulated because so many more people are visiting them, so starved has our species become on a global scale for an intimate experience of nature. Many cannot afford the tickets to enter these parks, and now people can no longer camp in them for more than a few days without being evicted. The authorities have presumed that they may take something which belongs to all the people by virtue of legal grant and fiscal upkeep, and arbitrarily delimit the duration of how long our free citizens might enjoy the vast spaces of sanctuary these spaces were intended to afford to the world-weary. In light of all this encroachment into our freedom to roam, I have begun to observe an interesting trend where some people now wander amidst and restfully sit in cemeteries. The people, to whom I have spoken or of whom I have read who do this, are not morbid, nor do they harbor any bizarre necromantic motives. They have simply discovered that in cemeteries they can finally enjoy the relative solitude and peaceful interaction with nature that does not remain for them anywhere else in their accessible locale. Let us hope that, in the sacred sanctuary of the final resting place of our forebears, the officious boundary-monitors do not close down this final refuge for those of us who still seek to commune with the quietus of nature.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

The Woods, My Temple

Several years ago a movie called The Blair Witch Project came to theaters, and it became an instant cult film. It caught a certain sort of zeitgeist among suburban youth, playing upon the latent fears of a whole generation of white kids suffering from a severe lack of experience of the natural world in their upbringing. When I saw it with my friend to fulfill a sense of curiosity about the craze for this "home-made" horror film, I couldn't get caught up in it. In fact, I found the premise of the film insulting to what for me was most sacred. You have to imagine what it would be like for a person, say, raised in a traditional Christian denomination, where the physical structure of a church had always been a place of social warmth, comfort, and fellowship, and then experiencing a viewpoint where it is presented as just the opposite but without any foundation in fact. To leave this metaphorical scenario, I had been lucky enough to have grown up in the generation before the one that found The Blair Witch Project so compelling. I had grown up in the country, and for me, the woods had always been a place that brought me peace, inspiration, and a sense of wholesome refuge. The film I saw was an ignorant vilification of the woodland realm and its aura. I felt like I was seeing the ugly head of anti-nature Puritanism rearing up again, in a "cooler", "more hip" form. For the Puritans, the woods was the place of evil, the devil, the source of destructive wild energies, chaos. They too vilified the wilderness as a place of satanic religion. They failed to grasp that, in the woods (or forest, if you prefer), the presence of God can be felt far more powerfully and pervasively than in the artificially-created environments of sanctioned human activity. What I don't like about films such as this, is that it may have crystallized a viewpoint, perhaps subconsciously, in a generation of people, who now are working their way up the ladders of the professional workforce. They are making decisions or supporting decisions about how much of the natural environment gets preserved and how much of it gets erased. They may not entertain the superstitions of New England's old Puritans, but they may harbor an ill-informed prejudice that the places of wild nature are somehow not wholesome. For such people I can only say their souls are as ill-nourished as the proverbial philistines toward the world of art. Nature is the deepest well of aesthetic beauty. Nature unbound is the ultimate source of all lasting art. It is also a place that the fortunate among us think of as a temple, a place of original worship, where the imagination and spirit of homo sapiens must first have taken form.

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

It Happened In England

In the 1950s, the United Kingdom was in the process, like the United States, of modernizing its roadways for automobile traffic. Now, in the United States over the past several decades, there have been a number of cases in which American Indians have protested highway projects which threaten sacred sites, either because it is a place of holy pilgrimage (like sacred hills or bodies of water) or because there are human burials of a tribal nature located in the threatened locus. But to get back to the United Kingdom, there happened a most curious event in the southern part of England among a group of people whose culture had, by that point, undergone heavy industrialization and urbanization for over a century and a half. Traditional culture in the rural areas at this late date persisted only in fading fragments. Yet, when a neolithic mound was to be taken out to make room for a new highway route, the rough and tumble road laborers refused to demolish it. Their explanation was that it was a fairy knoll, and therefore sacred to the fairies. They would not show them any such disrespect as to destroy their dwelling. And so the highway had to be built around it. This story I first remember reading about in the introduction to Ruth L. Tongue's The Lost Folktales of England. It appears that the sacred landscape and the related appreciation of its animistic qualities (think of the "landvaettir" of Norse Mythology), die hard, even in the age of the atom.

Monday, February 22, 2010

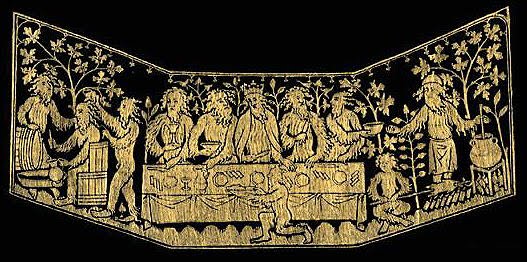

The Medieval Balladeers (and more)

There are scholars narrow enough in their appreciation of the Middle Ages who have made blanket statements to the effect that Medieval people hated the natural world, and saw it as the realm of the devil. These scholars claim that Medieval folk trusted and valued only what they could bring under their plow or the teeth of their flocks. This may hold true if the only sources these scholars are paying attention to are the theoretical treatises of unworldly monks for whom the world in general is an abomination, the realm of Adam's Fall. But for the people who actually lived on the land and in its elements, rather than in a tidy cloister with comfortable endowments from the Church and the nobility to write whatever clap-trap intellectually justified the subjugation of the world for power and profit, the view of Nature was rather different. Fortunately, evidence for this alternative view survives in the popular songs, secular lyric poetry and not least of all, the ballads of our own English-language tradition. If the poets of the Classical period appealed to a divine muse at the beginning of their works, the troubadours, minstrels and balladeers of the Middle Ages appealed to nature itself. The verse literature of the Medieval Period is rife with praise for the wild trees, wildflowers, beautiful undergrowth, songbirds and feral denizens of the woodlands, meadows, marshes and moors. The common people, the people not constrained by the utilitarian ascetic agendas of religious vows and ecclesiastical patronage, freely expressed their love of nature strictly for its own sake rather than for any practical use. Most Medieval people had an aesthetic appreciation of nature, and valued the fact that not all the world had fallen under the steward's itemized book of goods and properties. You can see that love of the natural world borne out also in the surviving tapestries and embroideries they created to bring beauty to their otherwise plain walls. And then there was St. Francis, who knew nature was beautiful and sacred on its own terms because it was as much of God and Man was. Its always nice to run across a true spiritual person thinking and moving free of the shackles of politicized institutionalized religion.

Social Darwinism

Man is quite foolish when he deceives himself into thinking he can follow a bare-bones model of nature and seize property and capital resources to determine who is fittest to prosper and lead the species into the future. Mutational improvements in genetics are random, and so in nature, there are no dynasties of rule among animal species. That is why competition is constantly shifting from one part of a given population to another. Yet human authorities are desperately trying to prove that less fortunate people in our society are so because of their genetic make-up, and therefore deserve to be in that condition, and therefore that it is a waste of energy to help them. This twisted line of reasoning stems from those who wish to construct a society of elite plutocracy, and their forays in attempting to substantiate this false doctrine will always amount to the contortions of a pseudo-science. History bears out the lie in their arguments. Humankind's greatest thinkers, creators, leaders, just as often come from the "common gene pool" as they do from any "aristocratic one". Let me compile a list of some of the indispensable commoners from the legacy of human progress: Archimedes, Socrates, Seneca, Aesop, Shakespeare, Lao Tzu, Jesus of Nazareth, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, Charles Dickens, Benjamin Franklin, The Beatles, Mozart, Beethoven, Alexander Graham Bell, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Keats -- I could go on into profundity. It is in the interest of the survival of the human species that all portions of its population be nurtured equally. If it boils down to survival of the cleverest at being greedy, what is the lasting quality of such a gene pool? Would the human race really be noble enough to be worth saving in the eyes of any fellow sentient race across this great universe of ours -- let alone in the eyes of a Supreme Being?

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Savage Nature

Certainly in the quest and competition for food, nature can be savage. We are even encountering cases of psychotic violence among such species as lions in the wild. The debate also rages as to whether human beings themselves have only a veneer of civility over a savage interior. Yet these considerations must be balanced against an equally strong force in nature for nurturing and social bonding, which the media, for whatever nefarious agenda, chooses to under-emphasize. Testosterone and estrogen can both be sources of chemically-fueled aggression, depending on whether one is male or female, but they are also pathways to physical vitality and therefore the foundation of spiritual vitality. Our cousins among the great apes do not act violently unless there is competition for mates or there is a trouble-maker threatening the well-being of the group. Most of the time potential aggression is sublimated through social bonding rituals and shared labor activities, including child rearing. Among the simians, peace is the preferred norm, and violence causes communal stress. It is not celebrated. Violence is only a necessary tool among many other resourceful social behaviors which are healing and nurturing. I myself have witnessed the capacity for kindness in animals that belies the sensationalistic stereotypes our media like to harp upon. Our family Rottweiler dog, by the name of Brutus, loved horses. He was in awe of them. When he would come to a fence, he would get up on his hind legs, resting his front paws on the boards, and the horses would go up to greet him on the other side. They would touch noses, snuffle each other, the horse very placid in its interaction, while Brutus would be wagging his stubby tail rapidly. I think his canine mind might have seen these great equine beasts as supernatural beings, perhaps as "big dogs" or "god dogs". He was always thrilled to visit horses, and made a bee-line for them. We had another dog, an Australian sheep dog, who rescued a foundling kitten, and nurtured it like she was the mom, and it her pup. It was quite a beautiful thing to behold. That animals are only concerned with savage needs to seize and protect a source of food of procreation, and not socially aware of the innate value of their fellow denizens is another falsehood. A second generation Rottweiler of ours, Luka, was running through the woods with me one day, when she suddenly came to a stop. I was puzzled as to why she would have halted in her headlong romp of joyous exploration, until I looked up, following the tilt of her head. Upon the broken top of a dead tree, perched a perfectly tranquil owl, not a feather ruffled from the thrashing movements that had brought us into its midst. Luke showed no aggression toward the stately bird, and the bird, just oscillated its head, calmly taking each of us in. Luka was mesmerized, but she did not try to jostle the tree. We left the wonderful creature to its peace. There are many stories like this in the annals we keep of daily experience. Do not allow the presumptions of the media prevent you from experiencing the equally vital tenderness of nature. Do not allow yourself to become alienated from nature because of media-manipulations that endow the natural world with exaggerated menace. The menace is a projection of our own collective psyche held captive by the perturbations of an unhappy culture. Welcome what is truly there, and develop your own more wholesome culture.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Whose Version?

The eastern cougar supposedly just barely persists in the dwindling refuges of the Florida Everglades. And yet this native feline predator once freely ranged throughout the various regions east of the Mississippi to the Atlantic Coast. In my neck of the woods, where this creature was known as a "painter" (dialectal corruption of "panther"), or (more colorfully) as a "catawampus", the species supposedly met its end in massive "round-ups" in which pioneer settlers in the region gathered by the hundreds, surrounded a patch of wilderness, and drove all the beasts therein to the middle where they were all mercilessly gunned down, from little squirrels to black bears. In this way the early settlers domesticated the land of what they viewed as annoying or dangerous "varmints". And so, the naturalist gospel states that the eastern cougar has been extinct from Appalachia for nearly two centuries. And yet the annals of folklore, from the time of firm settlement by Europeans to the present, have continuously recorded the presence of these large cats, usually in a melanistic rather than golden coloration. These sightings are all dismissed as "superstition", and yet if scientists do not seek them for study in the East, then they fulfill their own notion that this creature is indeed extinct. I once worked in a used bookstore, popular with the whole gamut of our local and even regional population. One day a young man and a middle aged man came in, asking for books on wild cats. I showed them where they might be found, and they then proceeded to tell me that on their recent hunting trip the two of them had encountered a big black cat the size of a cougar. In the course of the conversation I learned several things: that these two were experienced woodsmen, that they were natives of our region, that they were not college-educated, that their friends and relatives had reported seeing this beast repeatedly over the decades, and that they themselves believed what they had lately seen. Such men as these would no more mistake a black house cat for a cougar than you or I would mistake a rat for a groundhog. They were excited to find a picture of the creature in a book, of course from the Far West. Satisfied, they left without purchasing the book. No one educated them to presume that this species had gone extinct long ago in our region. They were from a very poor rural county. For them, the black cougar was a fact of their lives, just as robins feeding on worms in one's lawn. It only stands to reason. The mass-slaughter of the round-ups did not wipe out squirrels and other wildlife. The cougar, whether of the eastern or western varieties, is one of the shyest and stealthiest of all the big cats world-wide. If the greater presence of Man on the landscape (after the European arrival) made life more dangerous for this species, it would only make sense that a genetically recessive melanistic tendency would be suddenly favored, because it would give this feline added camouflage for night-hunting and day-sleeping in the shadows. If this creature still exists, the people living here do not need the stamp of approval by the scientific community to appreciate the crafty survival of this large mammal in the modern landscape, where so much of the farmland has gone back to wilderness.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

No Trace

I spent much of my growing up riding my bicycle or walking my dogs down a nearby country lane on the ridge where I lived. It a was narrow winding road bordered by copses, ragged meadows, hayfields, vegetable gardens, little houses and abandoned barns and outbuildings, semi-hidden amidst encroaching wilderness. It was very lightly traveled, and so it served as a rare zone for a dreamy-minded child or reflective adult to lose him or herself for awhile in peaceful solitariness or tranquil companionship with a friend or family member. The lane was bordered by trees that formed areas of cozy shade, making for colorful rows in the autumn, and also bushes that were fragrant in spring, berry-laden in summer. A highway bypass was built a few years ago, fully wiping out over half that little country road. There is not a hint remaining of its original extent, which ran all the way into the outskirts of town. It is now a short dead-end road overlooking a four-lane highway built by digging machines comparable to dinosaurs. Trucks just as large hauled all the earth, rubble and broken vegetation to parts unknown -- the very stuff that had once sheltered my imagination, borne my speeding or rambling bike wheels, supported the paw-steps and footfalls of our feet and those of the generations of dogs we walked there. Toward the end of this lost road, the whim of the highway crews left standing one great white oak that could have served as the mainmast of a clipper ship. Perhaps that remaining tree provides some indication of what once was. Yet I find it all so profound that an entire landscape, down to the very form of terrain, now exists only as a memory of mind. There are places of recollection that no longer physically exist, not even in the spots of their foundation. No future geologist will ever fully divine the original shape and extent of the ridge. The Pharos Lighthouse in Alexandria, Egypt (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) no longer stands (it has not stood for many centuries), but archaeologists can show you where it once stood. Yet of where down that winding country lane I once rode my bike on hazy summer afternoons or chased deer with my dogs on cool breezy evenings, I can show you nothing.

Monday, February 15, 2010

Microcosmos

In the region where I live the American Indian had left intact sweeping tracts of forest that literally dwarfed the first European explorers that entered them in terms of the height and girth of the old growth trees, being part of a continuous deciduous canopy that stretched from the craggy shores of Maine to the Bayous of Mississippi. Now there are only minuscule fragments of this original temperate forest system. Yet to know this is not to despair. There are beautiful secondary growth forests that have grown up in the aftermath of decades of irresponsible clearing for pasturage on the hills, a practice that came to an end with the collapse of a marginal system of hard-scrabble farms during the Great Depression. Because of ensuing decades of allowing the land to return to its true nature, animals once scarce or absent even as late as the 1950s have returned to flourish. A plethora of oaks, maples, beeches, sycamores, and hickories have returned to our foothill country. There are lovely woodlots everywhere that a person can step into and lose him or herself for fifteen minutes or an hour. Yet even if one has no ready access to such places, a tree or two in one's own yard or local park can take the receptive soul into a microcosmic appreciation of our woodland heritage. A single tree represents a rooted reality of greater things that may come in its wake. One day again we may have a new old growth forest, though it may be more a lovely checkerboard of neighborhoods and (as the Canadians, Brits and Aussies say) bush rather than the gargantuan swath it once was. Each little tree and the wee bird that alights upon one of its twigs embodies the creative singularity which begets an arboreal sea.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

The Inner Salvaticus

If Rousseau thought eighteenth century folk needed to get in touch with their natural selves, then the call must be put out again for 21st century folk. We may be more in touch with our natural emotions and their significance to our quality of mind, but what about a healthy source for emotion and mental well-being of which we so often neglect to partake: our personal individual engagement with a natural environment? In European folklore there is the figure known generally as the "salvaticus" (a term form Latin), translated in any given vernacular as (in the literal sense of the phrase) "wild man", or in the archaic English tongue "woodwose" (from Old English: wuduwasa). Psychologists say this figure of the popular imagination serves to remind people of their origins in nature. Art depicts these wildfolk as covered with hair, adorned only with garlands and belts of leaves or wildflowers, wielding clubs, dwelling in the forests and wastes of Europe, living free with the wild plants and animals, occasionally abducting their civilized human cousins into their world of animal play and jubilant instincts. Often they are protectors of unoffical preserves of feral creatures and groves against hunters and lumbermen. They are not supernatural but mortal beings who raise offspring and are vulnerable the way hairless, cloth-wearing folk are. Howsobeit, there is also a spiritual salvatica in every woman and a spiritual salvaticus in every man. Children don't need to be told this. To cultivate this inner primal self, allow your imagination to embrace a natural setting the way a child would. Do not impose your mental trappings upon it -- allow it to inspire you of its own elements. Dance and sing among the trees like a woodwose of yore!

Vulnerable Strength

The Red Fox of our northern hemisphere is the smallest feral member of the Dog Family. To the human eye this mammal comports itself with a fascinating combination of dog-like and cat-like mannerisms in locomotion, stalking and play. The tail of this creature makes up a significant part of its weight, providing its limber body with a counterpoise than enables it to achieve feats of agility. The red fox can spring and hop as well as any feline. Their immature offspring (kits), come in delightfully (and protectively -- think camouflage) mottled color patterns, unique to each individual, combining black, russet, gray and white splotches (though I observed one kit that was entirely black). As predators they must compete in particular with their larger dog cousins, who will kill foxes, given the opportunity. Here in the East, they are threatened by the spreading encroachment of coyotes, who have crossed the Mississippi and are finally filling the gap left by extinct presence of the wolf in our part of the Country. The fox must have meadows and woodlands to thrive, and even in good conditions, they spread themselves thinly on the landscape. In Ohio where I live, a naturalist years ago once told me that there averages one fox family per seven square miles. I no longer know if this holds true with the pervasive encroachment of coyotes. The fox is a clever, shy and efficient creature, but they are vulnerable even without the madness of man impacting the landscape. In European folklore they are the "underdog" or "antihero" in the tales of Reynard or Reinhardt Fuchse, while in Asia (especially Japan) they are viewed as mystical, sometimes supernaturally dangerous creatures (like the way American Indians view the coyote), but whatever man chooses to ascribe to them, they are resourceful creatures who intelligently nurture their young and will take a moment to play like any good hound or house cat given the opportunity. They are vulnerable, their existence fragile, but they are wonderfully real, and when I am lucky enough to see one, I consider it a blessing and good omen to my life and mind.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

The Finest

The white oak embodies the pinnacle of woodland evolution from its origins as a meadow in the northern temperate zone of North America's Eastern woodlands. It is the finest hardwood, the slowest growing yet the sturdiest. It produces acorns only once every three years. You will not find groves of these trees like you would other species, as its rarer and less acidic fruit is eagerly devoured. It grows tall, straight and well-anchored. It is the friend of squirrels, birds and deer for food and shielding. Its leaves are round-lobed and medium-sized, and they turn a golden white to pale butterscotch color in the fall. The bark is very finely grooved. They were prized for ship's masts on the clipper ships. When you enter a place where these trees grow, you enter a world of natural venerability and serenity. The finer things in life are not always what are called the "greatest". The more refined are the things that invite you to see and listen and think carefully, and the reward for the soul is treble that of the things that are more immediately apprehended for more spectacular or imposing qualities. This is the tree for the American druid, and all the things that relationally go with it are its family. Here is a real grandfather tree in the woodland, or one in the making. Behold it, protect it, nurture it, and sit beneath it (whether be it young or old) and enjoy its animistic presence.

Friday, February 12, 2010

The Beginning

Welcome to a blog that proposes to discuss the interrelationships between the natural world, language, literature, folklore, myth, music, art, popular culture and everyday experience. The title of this blog relates to the subtle strength of these two species, one plant, one animal, both of whom require a stable ecosystem to thrive, but which provide quiet beauty and meaning to the meditative watcher, walker, and open-souled druid of the modern day. They are also the earmarks of the natural environment where I live in southeastern Ohio. I hope many of you out in the blogosphere will choose to accompany me on a wanderer's journey.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)