Sunday, November 6, 2011

The Lost Promise of Bronze Age Crete

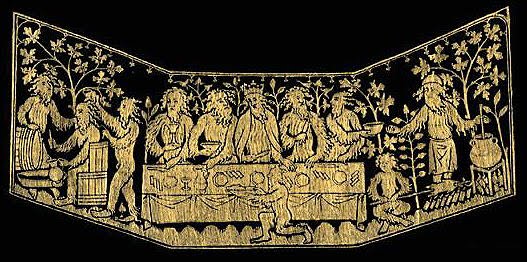

The ancient Minoans are one of the most enigmatic cultures of the World of Antiquity, exceeded perhaps only by the Etruscans. We need to be clear whom we are talking about. The Minoans were the aboriginal peoples of the Island of Crete, who had a language distinct from that of their Greek neighbors with whom they shared the Aegean Sea. They had their own written language, uninformatively referred to by scholars as "Linear A", which is still untranslated. What remains are their buildings and frescoes and references to them in the written records of their trading partners, the ancient Egyptians. What we know of them from their later Greek conquerors (who submerged their culture as successfully as the Romans did their predecessors, the Etruscans) is seen through the distorted lens of prejudiced myth, with such tales as that of King Minos and his monstrous son, the Minotaur. For the Egyptians they were reliable trading partners, who brought to the ports of the Nile Delta not only the finished products of Crete itself, but also the raw materials and artful trade goods the Cretans obtained from Mycenaean Greece and the barbarian reaches of the illiterate Balkan tribes. The archaeological evidence is extraordinary in its implications by how the Minoans differed from all other cultures of the time. They possessed no military architecture. There are no accounts by their literate Eastern Mediterranean neighbors, the Hittites, Greeks, Lydians, Phrygians, Phoenicians or Egyptians that they ever made war upon anyone. Their frescoes and objets d'arte possess no martial symbolism. In fact, their scenes depict elegant features and creatures of nature, acts of recreational athleticism, and figures and expressions of dignified and unsuppressed womanhood. There is now geological and structural evidence that the cataclysmic volcanic eruption of the island of Thera to their north (today's Santorini), generated massive tidal waves that devastated their coastal cities and wrecked the merchant fleet that harnessed their successful international economy. In their disordered societal condition during the aftermath of the tsunami, Mycenaean raiders descended upon their defenseless ruins of habitation and plundered and pillaged what remained. From there on, Minoan culture ceases to be expressed in the archaeological record, and is replaced by the artifacts and writing typical of the Mycenaean Greeks. Crete ever after became a Greek island, and its martial Greek overlords figure in Homer's war-epic, The Iliad. Today, urbane scholars like to downplay any form of idealism of the Minoan culture, finding it impossible that such a society of peace could likely have existed. They assume that one day, when they finally discover the key to translating Linear A that they will discover their cynical expectations proven: perhaps a dark revelation of inventory catalogs detailing military materiel and accoutrements. Yet if they truly were a warlike race, they would not have been able to resist displaying their love of martial prowess in art, which simply does not bear this out. Warlike cultures also tend to minimize the role of women, but the beautiful murals and sculptures of female members of their society do not betray this attitude in any form. Their warlike neighbors in North Africa, Asia Minor and the Levant were not bashful about recording their wars with other peoples, so why would they have neglected to mention any piratical attacks they had repelled from the Minoans? No, the Minoans appear always to have been peaceful traders before their island was settled by the Greeks. Could the apparent social equality between men and women reflected in their art have something to do with the balance of peace and successful trade they maintained for literally thousands of years during the Early Bronze Age? What both history and contemporary anthropology have both taught us is that the more warlike and violent a society, the lower the position women hold in society. The naysayers can declaim all they want, but their cynical speculations carry as little weight in the objective mind as the neighing of goats. In fact, the archaeological evidence has to be completely ignored if one wants to posit that the Minoans were just like everyone else. So let us not allow the "urbane" scholars of minimalist interpretation to blot out the legacy the Minoans have left for us: the hope of a society that has cultural vigor, the sexes on an even par, long-term economic stability -- and no war.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment