Saturday, May 14, 2011

So Called "Indian Time"

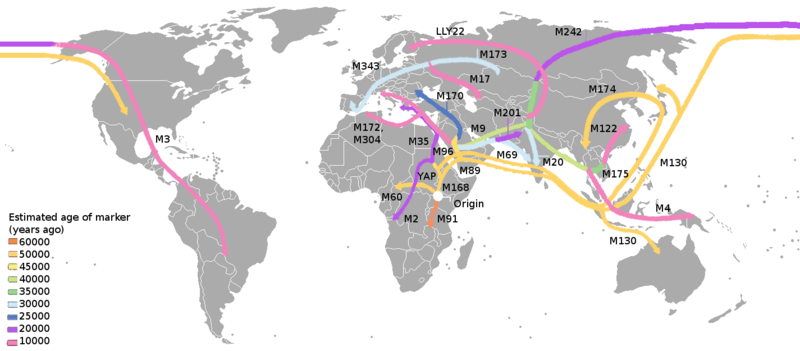

"On Indian Time", a common phrase, sometimes used pejoratively, occasionally with affection, more often used in neutrally descriptive contexts, describes a Eurocentric reaction to the tempo by which native peoples in North America executed their daily tasks. Even by the 16th century, the clockwork mentality of European culture was gelling, and this at the time when significant social relations were really beginning between Amerindians and European colonists. Actually, "Indian time" was a perspective on time shared by all human ethnic groups before entering an urban-oriented tenor of life, whereupon intense schedules of trade trickled down to affect even rural farmers. Of course, at its onset, this more structured, scheduled form of existence was not so rigid and ruthlessly efficient as it is today, but it was in comparative terms with tribal horticultural/hunter-gatherer cultures it ran up against. The population pressure and resource-hungry economy of European civilization was the real root of difference between the European sense of time and the way of life they encountered among the aboriginal inhabitants of the New World. Increased mechanization with the emergence of the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century only widened the gap in attitudes toward time and work between European Americans and Native Americans. Yet if we think of "Indian Time" as really an unstructured, freer sensibility of the use of time to pursue constructive tasks of thinking and doing, it is the most valuable use of time in which human beings can engage. It is in "Indian Time", that many important, often breakthrough innovations are achieved, and have been for tens of thousands of years of human cultural development. Yet even on the most practical terms, a more open sense of time was exactly what was needed when, for instance, hunting was a key component of survival; hunting not for sport but for real subsistence required patience, unstructured time, and the keener level of observation and perception only such an "un-scheduled" approach can beget. On the other hand, if "Scheduled Time" is the polar opposite, the utility of that acute form of time sensibility lies in the maintenance of the mega-complex of routine needs in an efficiently coordinated society on the competitive fast-track. Yet if the latter is the world of time in which most of us now exist, we must still (somehow) leave room for the former, older sensibility of time, otherwise there will eventually be no more significant progress in human thought and achievement. We must leave time to "play with our imagination", or we will stultify from an excess of efficiency. The utter domination of the scheduled existence inevitably leads to the cultural nadir we call "stagnation".

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment