Wednesday, April 28, 2010

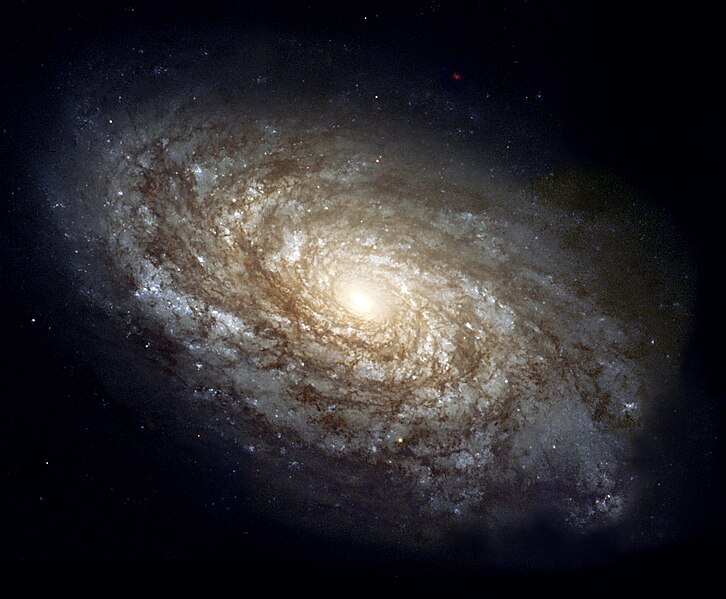

Who wiill be the Custodians of the Custodians?

We're the most intelligent species on the planet, we have self-awareness, and by fait accompli we have been duly appointed the "Custodians of Nature". I do not need to get into the well-established bundle of insanity that makes this responsibility so ironic. But in case you're reading this as a fresh visitor from another planet, I will briefly summarize the behavioral tendencies that makes us, "Nature's Jailers", a walking cabinet of conflict of interest cases; we the custodians engage in: destructive political and commercial competition for Nature's resources, extractive practices driven by corporate greed (which results in a myriad species going extinct each year), an unfair balance of ownership of the Earth's resources (a legacy of colonialism -- which forces impoverished peoples to farm marginal land turning it into desert), religious and male chauvinistic resistance to responsible birth control (which creates population densities that regional environments cannot support), and our shackled dependence on burning oil and coal for energy (which creates devastating drought through climate change). All of these factors make the human race the poorest example of what it is to be caretakers of anything so rare in the universe as a a planet with an actual biosphere. How is it that we evolved to be technologically capable of actually harming the whole planet's ecology, but did not evolve a concomitant awareness of and respect for our debt to Nature? But then again, it is not as if we treat our species any better than they way do the other creatures and features of this planet. If in all the time we have walked the earth we have never managed to learn to take care of each other except perhaps in general terms on a family level, and occasionally (under certain limited circumstances) on tribal and national levels, how could we be expected to act altruistically for Nature herself? Still, the fact that we actually have the capacity to look beyond the immediate concerns of survival and reproduction, that we can sense the beauty and profundity of the whole order of life and discover the chemical physical dynamics underlying it, it would stand to reason that a desire to protect, maintain and nurture our world and each other would follow. Perhaps that's where education would fit in. Too bad in America we're more concerned about our children being rote learners trained to see tests as the end-all of their schooling. But what if we allowed our children to appreciate all that there is to learn out there (not just what the politicians tell them to pay attention to), and develop the dynamic mental capacities to engage with those beacons of mystery (i.e., critical thinking tools)? Then the answer is solved as to how we can create a custodianship for the custodians of Nature (i.e., an ethical foundation that polices the ecological caretakers). The custodianship would be education itself. Those so educated would police themselves. An educated appreciation of the majesty and fragility of the web of life that binds us (and the massive lifelessness that surrounds us in the greater universe) would make our actions conform to a resultant ethics operative within the conscience itself. But if we keep our educational system running like a great bridge to nowhere, the "Bad Jailership" of the planet will be free to continue. These Bad Jailers know full well that there are not enough properly educated people with an adequate ecological perspective to oppose them politically. So they continue to merrily strip the planet down to its bones. These "Custodians" need Custodians.

Friday, April 16, 2010

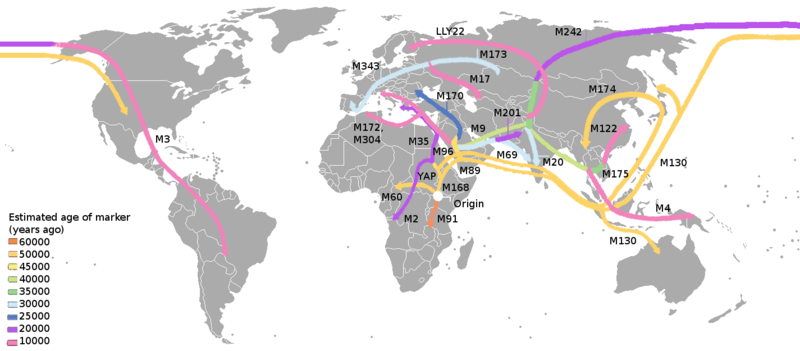

Just who Painted the Upper Paleolithic Masterpieces?

Well, scientists will tell you that the Cro-Magnon people composed the incredible painted art, which survives in deep caves scattered across France and Spain, from a period of activity extending from about 35,0000 until 13,000 years ago. Scientists otherwise refer to these particular human beings as "archaic humans" or "early modern humans" or homo sapiens sapiens cromagnonensis. The genius of these creations is the combined lightness of line and richness of color in the depictions, not to mention the three-dimensionality, dynamic poses and anatomical accuracy in the execution. The subject matter is principally of herding animals (some of which are now extinct), such as wild horses, woolly mammoths, aurochs, ibexes, deer, bison, etc. The "canvas" is often of the most challenging sort, being the rather uneven and awkward surfaces of undressed stone that naturally form the walls and ceilings of caves, some of which are sea-caves! More ingeniously, these prehistoric artists have often chosen and adapted peculiar natural abstract (though imaginatively evocative) forms in the surface of these caves to enhance the three dimensional effect of their realistic subjects. All of it was done with flickering torch light, there being no benefit from natural daylight at their degree of remove from the Earth's surface. Coming from humans that are many thousands of years away from having any need of writing that we might otherwise know them, it is a profound link of understanding with the intelligence and values of the distant forebears to the present state of our species. It should not even be a concern that we should have to make any assumption about the color of the skin of these human beings, but in light of the latent racism raising its ugly head across America today in the form of the Tea Party movement, it is a matter that should be explicitly revealed. In point of fact, Europe was settled by groups of modern human beings from Africa some 50,000 years ago. At the time human beings made these paintings, our own DNA reveals that there had not been enough time for the mathematically calculable genetic drift to occur for these prehistoric people to look anything specifically like the average native European living today. In short, the master artists who painted all the exceptional paintings of such places as Altamira Cave and Lascaux Cave had a high melanin content in their skin and kinky hair. Need I be more specific? They were Negroes in the phenotypical or "racial" sense of that word. Gradually, these people would acquire lighter and lighter skin, and tangentially straighter hair over the succeeding millennia as an adaptation to the lesser quality of sunlight in Europe as compared to the plentiful sunlight under which the ancestors of every human being alive today evolved in Africa. This is a very small matter for those of us who realize the illusoriness of defining people by superficial physical differences, but I recommend the following book (which addresses itself to far more important and fascinating questions of human evolution), and which establishes the scientific truth of what I have just imparted: Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors. Written by Nicholas Wade. Published by Penguin Books. Copyright 2007.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Healthy Shame

"Shame" in its original sense as a plain English word is merely the equivalent of words such as "modesty" or "humility", derived from the Romance languages. There are unhealthy forms of shame, for instance: feeling ashamed of one's ethnic origins or economic status, feeling ashamed of one's natural physiology. These forms of unwarranted shame are very common in our culture. But there is a healthy sort of shame that is strikingly absent, and it is to our harm: shame for showing disrespect or lack of consideration for the fellow members of our species. One can argue the point even without reference to religion: we can look at the examples of other animals (O, yes, we are animals too you know, and we should NOT be ashamed of that!). I could cite a myriad examples of how intelligent creatures look out for each other, to the degree that they will even, when necessary, engage in personal sacrifice. A person might say it's all instinct, but not if you witness it in action. There is something more there resisting the severity of the heartless universe. Bio-chemistry alone cannot construct a mind with the will to make and maintain something beautiful in the face of battering nature. Perhaps the strongest case for this argument can be found in the Emperor Penguin of Antarctica. I do not believe the story of its yearly cycle of survival and self-perpetuation can be better told than in the British documentary series, narrated by David Attenborough, called, Planet Earth. I advise you to buy this series or borrow it from your local library, for the profound story of this creature and many other forms of life. It will do your soul good. But getting back to this specific species of penguin, I will remark upon the implications of what I learned, and not spoil the story for you yourself to discover. Suffice it to say, this bird, this animal, this collection of special beings puts forth the most tremendous degree of cooperative effort despite grinding suffering at the hands of nature, and all for the sake of continuing its kind. There can be few other creatures who endure more than they. One might remark, how is it worth it to them? They must be too stupid to know any better! But then one observes the way they appreciate the payoff, the way they care for those young ones they miraculously bring forth and raise in one of the most inhospitable environments on Earth (but also the only place where they might exist). Their endurance of bitterest weather for months on end to incubate their eggs, and the way in which they collectively preserve each other's lives in the process of this incubation, is pure spiritual beauty. Their love of their hatchlings is equal to this preceding effort. To know what they pass through, to see the life they assert in the teeth of chaos, should shame any human being to the tender arches of their feet. Though our own kind is riddled with members who have been dealt with harshly by the genetic roll of the dice, we collectively as a species, are one of the most fortunate on this Earth. If we were to do a tenth of what the Emperor Penguins do for each other toward our fellow human beings, we might begin to be worthy of the gifts we have been dealt in our evolution.

Monday, April 5, 2010

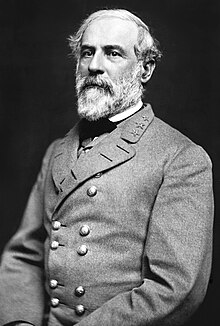

How to Judge a People

Throughout history human beings have stumbled upon a revelatory fact: the actual people of a political power may be quite different than the political power over them. Ironies form when you find a basic human affinity for someone you have been told is your enemy. In more recent centuries the basic agreement between human beings as opposed to the ambitions of political entities has come across most obviously between fellow scientists across the nations. In the Middle Ages, it was between fellow churchmen and churchwomen across feudal states promoting the cause of peace and compassion. During World War I and the American Civil War, Christmas was sometimes celebrated between opposing sides. There are World War II veterans and elderly civilians from eastern and southeast Asia who speak truthfully about how ill-treated they were by Japanese soldiers, and yet when General MacArthur occupied Japan to help them organize a new state, he found the common people of the civilian population more than ready to democratize, because they had been utterly unhappy ever since the imperialist military regime had mounted a coup d'etat over their democracy back in the mid-1930s. You cannot accurately (let alone justly) judge a people by the behavior of their government, even if that government claims to act by the will of the people. If you don't actually have the privilege to get to know a real live person from another country, another way to gauge the nature of their humanity is to read their poetry that relates to the natural world. It is in such poetry that clusters of refined spiritual qualities may be discovered. A great about thing about nature poetry is that it tends not to be a medium where poets seek to slip in propagandizing (and therefore hypocritical) airs. The natural world is neutral territory, by the very essence of its subject matter, a genre immune to the abuse of art seeking political advancement or to affirm political power, and therefore its creative canvas is a far more honest mirror into the real soul of a people through the nature-poets its culture produces. The haiku tradition of poetry in Japan (begun by the pacifist Basho) is a case in point, and shows that cold-blooded militarism was not at the core of Japanese culture, but lodged in the aristocratic periphery. Likewise the Chinese poetry by such reflective, nature-oriented poet-philosophers as Li Po and Tu Fu bears out the humanity of the Chinese soul, whatever one might say about the dread qualities of their historical empire. The Persian-language poet, Rumi evokes a wonderful unity of spiritual insight and keen natural observation. While the British Empire was wreaking havoc across the world, the true heart of their culture, exemplified by such Romantic and Victorian poets as William Wordsworth, John Keats, and Gabriel Rossetti wrote poems endeavoring to awaken the soul of humankind to its moral mirror in nature. Likewise while the United States was engaged in the slaughterhouse of its Civil War and the ethnic cleansing of the American Indian, you had poets like Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson writing poetry about the healing and insightful qualities of beautiful nature. I could go on and on. However, just as the sharing of scientific learning is a cue to our basic and essential unity as homo sapiens on this planet, so also is the immediate appreciation we may discover across cultures in creative celebrations and explorations of the meaning of the natural world and human soul's place in it. Politics are a lie, but nature is ever true.

Sunday, April 4, 2010

Shame in the Game

A hundred years ago, all the farmers in America were organic farmers. A hundred years ago, the majority of the people living were farmers. They led simple lives, worked endlessly and even if the year had mediocre returns, they never went hungry unless their parcel of land were particularly small and poor in quality. Animals drew the plows and harrows, and human hands sowed the seed and reaped the crops, shucked the corn, threshed the wheat, and the wind winnowed away the chaff. The implements were handmade and could be repaired by human hands. Farmers, men, women and children, had to eat heartily to get through the day's demanding tasks, and none of them suffered from obesity. At harvest time, often the whole community would pitch in to lend in hand for what meant at least local survival for everyone, and there was a communal feast of thanks as repayment for the help. The overhead costs of farming were quite proportionate to the means of the farmer, and the farmer had a firmer hand on the quality of his fortunes. Riverboats and railroads widened the opportunities for the sale of surplus, and what they did not eat directly from the field or sell at the market, they canned so that the dinner table remained plentiful even in the depths of winter. If you've read my profile, you know I am a librarian. Working at the public desk, I hear many interesting stories. One that proved particularly thought-provoking for me was when an organic farmer pointed out another patron walking out the door, telling me that this individual had made a rather idealistic attempt at our most important and very ancient human endeavor of farming. He had tried to farm as people did a hundred years ago. In fact, he had managed a life of subsistence, which was as far as his ambitions went anyway. He was more interested in pursuing a way of life, rather than to actually make a profitable business of it. And yet, he suffered the aggressive ridicule, mockery and eventual shunning by his neighbors, who were also farmers. It became so psychologically disconcerting that he moved away and to attempt a different means of life. The fact of the matter is that, while a farmer, this man had not put himself in debt for the purchase of copious amounts of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, expensive farm machinery, fuel, repairs, etc. His only real cost beyond the sweat of his brow was the proper care of his beasts of burden. It is true, from the story I heard, he did not get the returns that his neighbors did, a point they made to him with derisive humor. And yet, he might have made a life of it, if his neighbors had been decent human beings, or if had managed somehow to ignore them stoically. And yet, we are all ultimately dependent on community. Social ostracism is a powerful and devastating tool, so I do not fault this man, who dropped his simple agrarian dream after a few willful years of trying. So what got under the skin of his fellow farmers that they abandoned their proper role as kindly, supportive neighbors of this unoffending individual? I have thought long about this, for I heard it over a year ago now, and I can only conclude that what drove these other farmers to be so unkind had to be quite gnawing psychologically. I think it was envy. Every farmer is now the pawn of corporate profiteering on an interdependent set of purchases in order to practice the advanced technological and scientific art of agriculture, such that the pawns in this scheme can thank their lucky stars if they actually break even. Otherwise they are in debt up to their ears in bank loans to manage the expense of the costly purchases now deemed necessary to practice farming. And yet we have the examples of the Amish and Mennonite communities who do not use those things. Where these very old "counter-culturalists" hold an advantage over the poor individual of the story I was told, is that the Amish and the Mennonites have each other to support and affirm the lifestyle of simple agriculture. If outsiders deride them, they have their collective faith to shore each other up emotioanlly. All of this now brings me to another music review: Heavy Horses by Jethro Tull. This is very much a companion piece to Songs from the Wood, and came out the following year in 1978. Generally speaking, the album contains rather imaginative though no less accurate songs about life in the country, but its centerpiece is a stirring encomium of the draft horse (or as the English say, "heavy horse"). This is the creature that from the invention of the horse collar in the ninth century, C.E., has pulled the plows and other field implements of Western civilization until the final domination of the tractor in even the remotest corners of country life in the 1970s. To his credit, Ian Anderson, the leader, composer and lyricist of Jethro Tull, had become a leader in the cause to preserve the breeds and continue to use them, pointing out that one day "the oil wells will run dry" and the heavy horses would be needed again to perform their vital work. This album is stirring, moving, edgily humorous and a great round of bumptiousness to enjoy listening to at the dawning of spring in our world right now (whatever our planet's long-term troubles). The album has also been digitally remastered to perfection by Chrysalis records. If you like Songs from the Wood, you will equally enjoy Heavy Horses. Happy Pesach, Happy Easter and Happy Verna Tempora!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)