Thursday, June 30, 2011

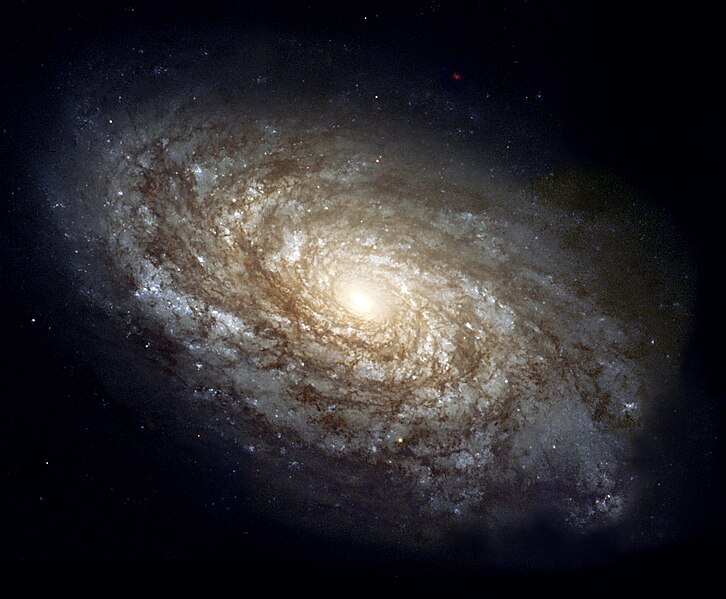

We Are So Much More Than They Give Us Credit For

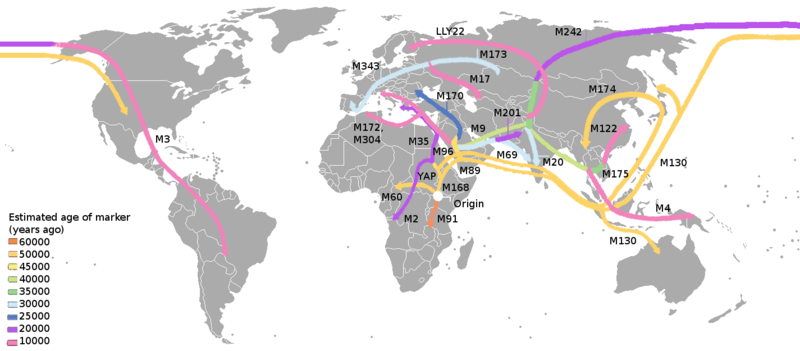

I recently saw a "documentary" on a major cable channel that purports to educate its viewers on what will happen if a country like America were faced with a pervasive national disaster. With a panel of political scientists, sociologists and resource analysts, they have come to the firm conclusion that America would immediately disintegrate into predatory anarchy. Government would rapidly abdicate its role of protecting the vulnerable against the sociopaths, and people would resolve themselves into violent gangs for mutual protection. No other scenario is offered. Is such a projection really intended to be "informative", if it assumes without argument that such a complete functional and moral breakdown of our society will occur? If it is so carelessly false in its projections, then this program is an example of fear-mongering, and what is the purpose of fear-mongering, especially during a time of economic recession and global climate change? Does the conglomerate that owns the channel that produced the program want people to lose their faith in civilization and go out and buy a stock of guns and ammunition? What else can one conclude? But putting aside the motives of such a "socially scientific" documentary of "how to survive the ultimate human disaster", be it from a global pandemic or a solar super-storm, or what have you, is it really true that most of us would just psychologically collapse and descend to the level of savagery? Is all the touted religiosity of the American public so hollow? It is prevailingly evident that most people follow the just laws of our land not because they fear punishment but because they believe these laws enhance the mutual stability and well-being of our shared existence. So would we really allow the sociopaths dictate the conditions of our lives during whatever period that our public resources are challenged? If this is so, we are not fit to take pride in anything our culture and society claim to stand for. One would conclude that all our worth is but a sham. But I do not believe this to be true. America, like any country committed to a just purpose, is the product of many centuries of progressive moral development. If our progress is admittedly under constant harassment by vociferous cynics and well-placed rogues, there are still many more of at least good intentions (even if not always wise answers) who are opposed to those who would lead us into corruption. In short, I do not believe that most people are burning for any imminent opportunity to destroy our peaceful society at the first sign law and order cannot be fully enforced due to a crisis. Even people of different political views, if they are sincere in the higher purpose of those views, will come together in a crisis and help each other out, regardless of the background of their neighbor in need. A common humanity will assert itself. It is fundamental to a normal and healthy human nature to form a cooperative and compassionate community for common success. We have evolved from bands and tribes over hundreds of thousands of years. We are a social animal. There have been other crises large and small in America's history, and the helpful people in those historical situations always far outnumbered the looters and murderers. We must not lose faith in each other and our mutual capacity to band together in a humane way under difficult conditions. The sociopaths have always been in the minority. Were it otherwise, our species would have destroyed itself long, long ago. That we survive is because people of goodwill have always prevailed. What we must guard against are those, for whatever political purpose, wish to psychologically condition us into an artificial attitude of distrust and demonization of our fellow human beings. Should any of us be faced with a geographic crisis, we must not give in to the deception that the only answer is "every man for himself". Most every person facing that crisis wants the best for one's fellow in danger, because "do unto others as you would have done unto you" is more than a mere ethical dictum. It is the expression of what people of sound mind instinctively desire for each other, because we are not a mutually hostile and merely convenient association of selfishly competitive "lone wolves" (my apologies to the wolves, who in actuality are not socially atomized). Those few who lack the capacity for empathy will socially retreat before the constructive behavior of mutual assistance during a time of trouble. The media-driven concept of "rugged individualism" is a load of bunk in terms of its practical much less popular appeal, and can only work as a philosophy for those in a position of independent wealth and security. People who believe that walking all over others to get ahead is something to be proud of because it involves clever ruthlessness have very few real friends in this world, and far fewer when the chips are down. In short, sociologists buying into this counterfeit ideal of a cutthroat business world cannot use it to form the basis of any sound theory of what regular human beings on the sidewalk will do when met with a collective danger. In the healthy psyche, crisis will inspire a beautiful altruism. It is deeply rooted in our collective being. Think of how human beings come out to help each other when a tornado has passed through, or offer assistance when someone down the street is laid up after a surgical trauma. These little acts of goodwill are exactly the stuff that neighborhoods and cities and entire regions use to re-knit and reassert the fabric of community when faced with a larger crisis. There is no difference, whatever the scale. The will is the same, and the response will be the same. Our desire for social order is encoded in our DNA as well as a natural expression of our very souls. We are not mere beasts. We are human. And come to think of it, most beasts treat each other darned well when faced with difficulties -- they nurture and protect their injured, undernourished and vulnerable members (even outside their own species, given the right circumstances). Can we do any less, as superior as we consider ourselves to be in terms of intelligence and moral discernment?

Monday, June 13, 2011

No Sacred Cows Please (Except Real Ones)

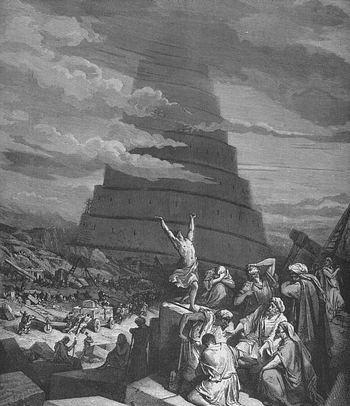

There is no human endeavor, no matter how potentially noble, beneficent, inspiring or at least in some way useful that is beyond corruption and misuse. There are athletes who take steroids. There are politicians who have been bought and sold. There are high profile actors who are callous womanizers. There are popular musicians debauched on hard drugs. There are unfair tax laws that benefit only the wealthy. There is unfair favoritism of the economic elite in government. There are unworthy people protected by various organizations. There are religious leaders who are complete hypocrites who bilk their congregations. There is irresponsible use of natural resources. For every good person and good effort there is its opposite in every sphere of human experience. In a democracy, a free press and a free academy are necessary to reversing the encroachments of corrupt influences through factual exposure, intelligent criticism and constructive analysis to restore morally and ethically responsible practices, means of accountability and regulatory monitoring to protect the vulnerable from harm. Now we have political pundits calling upon the American public to accept a new notion: that the art and practice of capitalism should be above criticism, correction and regulation. To be clear now, capitalism is just a means of acquiring the material goods to generate productive economic activity. It is a potential strategy of survival, success and social utility. Nothing more, nothing less. It can serve the good of society, and it can be just as easily twisted to serve the ill, just like a rigged carnival game. There is nothing inherently virtuous or indelibly perfect about the art of capitalism. It's just a social tool. That's it. And it has a long history of both broadly beneficial achievement and pervasively abusive exploitation. It attracts humans good and bad in its varied aims, like all human forms of activity. Therefore watchdogs and laws are necessary to prevent it from doing the worst kinds of potential harm, such as an aggregation of too much wealth in too few hands, which inevitably has a corrupting influence and bad effects for the laboring masses. If we shut off our brains, and shut off the power of government to protect regular people from the powerful on this issue, then we are saying that capitalism is more important than democracy. If we say capitalism can do no wrong, then we are endowing it with the perfection which God alone possesses. In other words we are falling into a trap we were warned of long ago in metaphorical terms by both the Jewish and Christian religious testaments: do not make a god of Mammon (a pagan deity of wealth) lest you destroy all that the one true God (who teaches us love, compassion, truth and social justice) intends for us and our moral well being. A perspective based on either spirituality or reason arrive at the same conclusion: there is nothing so pure that it is above constructive criticism and even legal correction. We are a species endowed with the power of both reason and conscience, and therefore given a mission to rise above savagery. We should not excuse, ignore or sanctify anything that falls away from the promise of that endowment of higher purpose, whether it came by biological evolution, the will of God, or both. In democracy there are no sacred cows, in the metaphorical sense. But you are free to hold a real member of the bovine species as sacred from the slaughter, if you are so religiously or ethically inclined. Human nature is a mixed bag, and its checkered nature should never be blindly ignored, in either politics, entrepreneurial practice or education. There are criminal minds among the rich (wealth has nothing inherently to do with legitimacy) as well as among those below them. Capitalism can be a good thing, but only if it is held in equal partnership with the principles of democracy.

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Leisure and Puritan Guilt

A contempt and animosity toward leisure has been a part of American culture through its Puritan heritage, inherited by certain elements of the middle class, and formerly held among the old wealthy families of the Northeast. Leisure was identified with idleness, the proverbial "devil's workshop". Only in constant work could evil temptations be held in check. To be sure, such a formula of tireless commitment to "divinely ordained labors" could work toward personal success. Witness the famous New England families who began as simple religious separatists of dour intellectual disposition in the seventeenth century, and by the nineteenth century, they had become captains of industry, political reform and advanced jurisprudence. Nowadays, it survives among upper middle class circles of Puritan heritage (even if no longer Calvinist in religion), slamming American society with such pronouncements that our "leisure" comes at the sacrifice of the developing world, or citing certain exploiters of the welfare system as typical (when in fact most use it as a necessary and temporary safety net from homelessness and hunger). To be sure, vulnerable people outside America who cannot escape the juggernaut of the global economy are often tragically sucked into lives of unregulated labor, often working dawn to dusk, often without days off. Yet the ancestors of these same workers once had stable traditional cultures of self-sufficiency where leisure was a part of life to serve as a healthy counterpoise to life's necessary demands. As for American leisure, those that enjoy it in our surviving middle class and working class, have it in balanced proportion: two days off and evenings off. Unions fought hard for that time. Some few even still get a week or two of vacation a year, and there is certainly nothing wrong with being restored by getting away from grinding routine for awhile. I cannot see a causal relationship between (on the one hand) regular people who work forty or more hours a week, and (on the other hand) greedy corporations in developing countries who employ people without any laws for fair labor practices to impede their exploitation of the area's human population. The Kalahari Desert's Bushmen, whose culture is one of the oldest on Earth, have leisure built into their autonomous hunter/gatherer society. Leisure is important for renewing the mind and body, for allowing the imagination to play and discover novel patterns of thought, to properly assess the changes of life, to fully digest recent insights, to rekindle one's humor. I could go on about how it is actually an "angelic workshop", but I feel I have established the fundamentals of my point. I will close by pointing out that the people that might be suffering a negative form of leisure are actually the unemployed. The psychological torture of joblessness is no leisure at all. We have thousands upon thousands of skilled, semiskilled and manual laborers who would love to see such centers of employment as the steel mills, the machinist industries, the ceramics plants, the household fixture plants, the electronic assembly plants, and the garment factories reopen. Most of those industries have moved to the developing world, but the people who have replaced our own citizens on the factory line do not enjoy the lives our union workers once had. There are no unions in the developing world. So we have an awful imbalance: people with no respite for leisure and people with onerous idleness. There must be a healthy balance to strike between these extremes, and it has nothing to do with leisure being a source of evil.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)